Are Corporate VPNs Really on the Way Out?

Many of the security concerns that made corporate VPNs a necessity in the 2000s are less important today. The rise of cloud-based SaaS apps have shifted the threat landscape, and security has broadly shifted to a Zero Trust model. Despite that, corporate VPNs still provide value and the companies that have them aren’t rushing to get rid of them any time soon.

Let me set the scene. As I write this blog, I’m streaming music on my Spotify app and listening via Bluetooth headphones. This is a pretty big improvement from my youth, which was full of scratched CDs and tangled headphone wires. But I still haven’t gone totally digital; behind me sits an expensive record player and shelves full of vinyl. I love my record collection, and I’m not alone. Even though vinyl could be considered more “outdated” than CDs, the (staggering) numbers show that they’ve got staying power.

That coexistence of the old guard and new is also taking place in the world of corporate data security. Think of records as corporate VPNs and newer security models such as Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA) as streaming music apps. The older technology is still around, but the bulk of the industry has shifted to remote connections that don’t require you to flip from side A to side B once the needle stops. (Okay, so it’s not a perfect 1:1 comparison.)

So what does that mean for the future of corporate VPNs?

The Rise of VPNs

The advent of the VPN can be traced back to 1996, when TechRadar writes that: “…a Microsoft engineer by the name of Gurdeep Singh-Pall developed the Peer-to-Peer Tunneling Protocol (PPTP). The goal was to use IP addresses to switch network packets and offer employees a secure and private means of connecting to their organization’s intranet.” This was before the widespread implementation of HTTPS, when unencrypted data intercepted via wifi was a huge security risk.

Kolide CEO Jason Meller remembers that time.

“If you were on a public Wi-Fi or something like that, all of your traffic was just in the clear. Anybody who was on that same network could see exactly what you were doing and what pages you were looking at.”

“Companies were really scared about that. They were like, ‘Oh crap, people are going to be able to see the emails people are sending, or they’ll be able to figure out stuff if they’re listening to the network. We need to make sure all the traffic is encrypted.’ That’s what a VPN allowed for.”

VPNs allowed workers to break free from the physical office building while still maintaining a connection to its servers and the corporate network. For a decade, they were as ubiquitous as trucker hats and frosted tips. But innovation stands still for no one.

The VPN Castle Comes Under Siege

By the 2010’s, the circumstances that created VPNs began to change. “The first thing that happened was mass proliferation of SaaS apps, and then the second thing was HTTPS got adopted everywhere,” says Meller. Cloud-based SaaS apps were hosted outside the company’s network, and had their own logins and security protocols, instead of being routed through the VPN. And HTTPS ensured that all internet traffic was encrypted, which made it harder to justify paying for VPN as a secondary form of encryption. “Once those two things became true, the argument for VPN really came into question. It was just like, ‘Okay, what is this really doing for us?’”

On top of that, VPNs were incompatible with a new technology on the rise. “The executives all wanted iPhones,” explains Meller. “They wanted to get their email on their iPhones, and they weren’t willing to go do this whole VPN dance. Not only were they not willing, iPhones weren’t capable of even connecting to a VPN back then. So they started punching holes into them,” Meller recounts.

Aside from new technologies making VPNS less relevant, they had (and have) a fundamental security weakness: if one is compromised, the whole network is at risk. VPNs are part of a security paradigm commonly described as “castle-and-moat.” It’s a model built around the idea of a private company network, protected from the internet at large by firewalls, IDS tools, and VPNs. Cloudflare describes the security model like this: “Imagine an organization’s network as a castle and the network perimeter as a moat. Once the drawbridge is lowered and someone crosses it, they have free rein inside the castle grounds.”

Forward-thinking security practitioners wanted multiple choke points to stop threats, not a single entry/exit. And the explosion of cloud apps enabled that–each had its own authentication process to control access, and even if one employee’s credentials were compromised on a single app, the others weren’t at risk. (That was the theory, anyway. In reality, poor password hygiene created its own security problems, and led to the rise of SSO and MFA.) Companies, specifically startups, faced a fork in the road: adopt an existing and tested security technology or lean into a burgeoning one that was still being figured out. But they didn’t all choose the same path.

Enter Zero Trust

In 2009, Forrester analyst John Kindervag coined the term Zero Trust.

Okta describes Zero Trust as: “…a security framework based on the belief that every user, device, and IP address accessing a resource is a threat until proven otherwise. Under the concept of ‘never trust, always verify,’ it requires that security teams implement strict access controls and verify anything that tries to connect to an enterprise’s network.” Clearly, this approach to security is at odds with VPNs, where all users within a given network are treated as equally “trusted” as soon as they authenticate.

In 2014, Google unveiled its BeyondCorp initiative, and Zero Trust gained credibility as one of the biggest tech companies in the world decided it was good enough to protect them. But not everyone was eager to embrace this shift, recalls Meller. “Really smart security people couldn’t quite wrap their head around it. You get stuck in your ways and you’re like, ‘No, VPN is how we’ve been doing it since the 90s, this is how we’re going to continue doing it.’” But that mentality wouldn’t play for much longer. “The threat landscape has really changed. You have to deal with insider threats or people who can get access to these VPNs and then they can wreak havoc,” says Meller.

Increasingly, startups started to circumvent VPNs altogether. The model shifted away from on-premises servers, closed networks, and office buildings, and toward SaaS applications, cloud hosted infrastructure, and remote work. “The reason we don’t use/have need for a VPN, is due to the fact we don’t have any self-hosted tools, software or servers and have a very IT literate team,” says Josh Barber, a Digital Specialist at 5874 Commerce.

Despite that, corporate VPNs (and VPNs more generally) still have their defenders.

The Companies Using VPNs Today

To get a temperature check on today’s usage of VPNs, we went to the Mac Admins forum for insights.

A VP of Technology at a small analytics company that uses a majority of SaaS applications still has a VPN in place. They boil their VPN usage down to: why not? “[VPN] was easy to implement, and easy to maintain. And it provides an additional layer of protection when using untrusted wifis.”

VPNs are also still the more familiar technology, and that can be useful for third-party compliance. As one IT manager said, “It’s easier to explain to auditors that your production environment is behind a VPN than it is to walk them through your zero trust platform.”

Some companies only keep VPN around because their customers demand it, as when a fixed IP is needed for a client’s server that has an IP whitelisted.

And of course, keeping on-prem servers–and VPNs to guard them–is still the most cost-effective option for some companies. That’s particularly true for legacy enterprises, although some younger and smaller companies also go that route. “We deal with large amounts of media that would be prohibitively expensive to have 100% cloud (print and digital publishing),” explains the IT Director of a medium-sized media company. “Hence the need for on premise storage and VPN to access that when not at one of our locations.”

In a recent interview Meller held with Databricks’ Director of Enterprise Security, Michael Tock, Tock discussed the delicate balance of choosing between Zero Trust and VPNs in a corporate security architecture: “If it’s your most sensitive data, your crown jewels, do you feel comfortable with the risk of putting it in the hands of someone else? Well, it might depend who that someone else is. If it’s a large company with a lot of experience, you might go, actually, ‘[Zero Trust]’s a sensible path.’”

Consumer VPNs come into focus

It’s forecasted that the global market for VPNs will reach an estimated $77.1 billion by 2026, but the future of VPNs may belong to individuals using it to watch geo-restricted media or to avoid governmental restrictions and surveillance. With 26% of respondents in one study using VPNs for personal use, the changing of the guard is happening rapidly.

Those same respondents shared that 47% of them opt to use a free VPN service—but as we know, nothing free is actually free. Since VPNs act as a gateway for a user’s internet traffic, they have the opportunity to inspect that traffic, and there’s a risk that data could be misused. So if you’re a security professional, you may actually be concerned about employees using personal VPNs on their devices.

The Cloud Looms Over the Castle

Sid Nag, Vice President Analyst at Gartner believes that the future belongs to the cloud: “IaaS will naturally continue to grow as businesses accelerate IT modernization initiatives to minimize risk and optimize costs.”

Taking those elements into consideration–modernization, cost, security–the path to Zero Trust becoming the default corporate security model seems inevitable. Yet, in our most recent survey of knowledge workers, 79% reported that their company used a VPN for security; it was second only to MFA (80%) and well ahead of MDM (52%).

From these results, we can predict that VPN will continue to coexist with Zero Trust security for the foreseeable future. That’s especially true for legacy companies and industries with specialized tools, in addition to typical SaaS apps.

“I’d love to migrate to a full ZTNA/SSE architecture eventually, but right now it’s too much work for not a lot of added benefit considering our needs and size,” says the VP of Technology we quoted earlier.

But while older companies may hang onto their VPNs, the new generation of remote-first startups won’t ever adopt them in the first place. Kolide is an example of a company that has never had a use for VPN, and increasingly is part of the Zero Trust ecosystem. Since our inception, we’ve watched as some of our customers have transitioned away from their VPNs, while others have held on– the choice is mostly a matter of a company’s specific circumstances. We don’t consider ourselves to be direct competitors with VPN, because even though some VPNs provide basic device telemetry, it’s not their primary function.

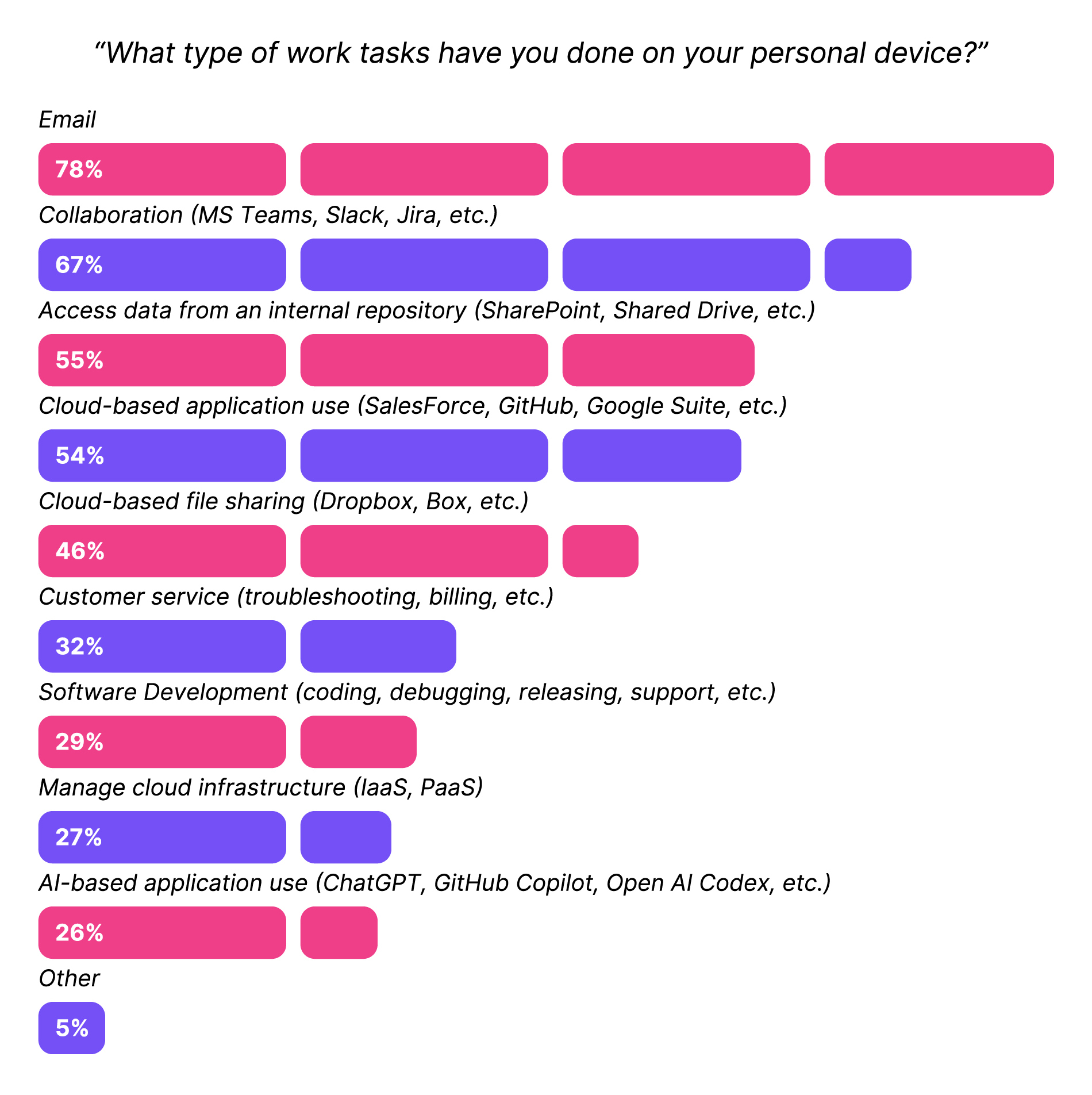

However, VPNs do present an unexpected security risk when they let organizations get complacent about what kinds of devices access their resources. In a nutshell: most companies don’t want any ‘ol device logging into their resources, because it could be infected with malware or belong to a bad actor. And since corporate VPNs are typically only installed on company-owned devices, it’s easy to assume that any employee with VPN on their device is only working on that managed, approved device. But it’s just as likely that employees use their work laptops for the VPN and use their personal devices for all those SaaS apps outside the VPN. In fact, our research found that 47% of companies let unmanaged devices access their resources, despite the fact that 79% have VPN. So while Zero Trust and VPN can coexist, the one can’t provide security for the other.

We’re not sure how long corporations will be able to hold off the transition to cloud-native methodologies like Zero Trust, but we do know it is not a zero-sum game. If you’re a VPN fan, breathe a sigh of relief—if it still has value, you can keep it.

VPNs may never be the star of the show again, but they’ll continue to have a role to play for individuals and organizations who need secure access to non-SaaS tools.

Security methodologies, like music players, evolve in unexpected ways. For every record that still provides value and an enjoyable experience, there’s a scratched-up mix CD withering away in a basement that no longer serves a purpose except for providing nostalgia of a simpler time.

Want to see how Kolide manages access to cloud applications with or without VPNs? Watch our on-demand demo!

Disclaimer I: Quotes from participants have been modified for clarity and brevity with their permission and acknowledgement.

Disclaimer II: The author of this blog has frosted tips.